COP24: A vital opportunity

Tuesday, 4 December 2018

The potential for anthropogenic carbon dioxide to warm the earth was first proposed almost one and a quarter centuries ago, in 1896. Growing concern as data emerged to support this theory led to the establishment of the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 1988. The subsequent 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro saw the adoption of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which committed to “stabilize greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system”. Earlier this month, at the IPCC’s 48th session, all 195 member governments approved the release of the IPCC’s Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C, which covered over 6000 scientific references and was written and edited by 91 separate authors. By its account, the world has failed to meet its UNFCCC aim.

The current COP24 meeting must heavily reflect on the recently released special IPCC report that was commissioned after the adoption of the Paris Agreement in 2015. The Paris Agreement put a figure to climate aspiration, pledging to hold “the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels”. The special report examines the impacts of the two stated values of 1.5°C and 2°C, looking at possible effects and possible solutions. As it happens, the new report illustrates not only how important the Paris pledge is, but also how much damage has already been done, and how much needs to be done – and quickly – to avoid impacts the report describes as “catastrophic”.

Meeting the Paris climate commitments

Even if all emissions stopped today, climate change’s impacts will still need to be faced. By 2017 the average global surface temperature had already risen 1°C above pre-industrial levels. This is changing weather patterns, endangering species and ecosystems, and threatening communities around the world. Enough CO2 is already present in the atmosphere for long-term changes to continue without any further emissions, such as continuing sea level rise.

The good news is that existing atmospheric greenhouse gasses are “unlikely” to, by themselves, lead to warming above 1.5°C. The bad news is how unlikely halting warming at 1.5°C seems to be. Per the report: “The rates of system changes associated with limiting global warming to 1.5°C with no or limited overshoot have occurred in the past within specific sectors, technologies and spatial contexts, but there is no documented historic precedent for their scale.”

Many pathways to limit warming to 1.5°C were analyzed, but none had a strong certainty of success. Achieving a maximum of 1.5°C warming requires a 45% reduction in CO2 emissions by 2030 as compared to 2010 levels, with net-zero emissions being reached by 2050. This rapid decarbonization demands massive changes across economic sectors and throughout society, affecting issues as diverse as electrification, agricultural practice, and lifestyle choices.

By comparison to this challenge, existing pledges fall woefully short. The nationally determined contributions (NDCs) pledged as part of the Paris Agreement would still lead to a 3°C rise in average global surface temperature, and will use the entirety of the carbon budget for a 1.5°C increase by 2030. This means that under current international agreements a 1.5°C warmer world will occur between 2032 and 2050.

Warmer world, warmer oceans

Climate change is the ultimate tragedy of the commons, where the actions of everybody affects everybody else. It brings with it changes to all the world’s global commons, including the oceans. To date, the oceans have absorbed 30% of anthropogenic CO2. While this has extended our carbon budget and prevented some warming, it has resulted in a change in oceanic chemistry unprecedented since the extinction of the dinosaurs. Increasing acidity occurs in tandem with increasing temperature, with both bringing huge changes to oceanic ecosystems and, in turn, everything that depends on them.

The IPCC makes explicit note of the impacts on the ocean. Temperature increases have been recorded as deep as 700m. Acidification and concurrent reduction in calcium carbonate concentration is occurring at similar depths. Marine heatwaves are becoming more common. Increased heat stratification and reduced solubility are increasing deoxygenation. Ocean currents and ocean upwelling are expected to change in difficult to predict ways as climate change progresses.

The impact of these changes on wildlife is devastating. Temperature rises and acidification threaten entire food webs. Acidification especially threatens mollusks, who need calcium carbonate to form their shells. Mobile species like plankton and fish are shifting ranges towards higher latitudes in response to warming, some up to 40 km per year. This disrupts existing ecosystems, which have to deal with new species in addition to abiotic changes. Immobile ecosystems such as coral reefs and kelp forests cannot escape warming, and thus suffer the most. Coral reefs are in particular danger. The last 30 years have already seen a 50% decrease in coral reef distribution and abundance. Bleaching events are set to worsen, and at 1.5°C 70-90% of existing coral reefs will die.

Coastal regions will be among the most affected in a warming world. Sea level rise will squeeze the range of shallow-water and ecosystems on the coast that are already being encroached upon by coastal development. It will also bring with it increased salinity in coastal land. More intense storms will destroy exposed ecosystems, and rising storm intensity and sea levels mean storm surges are already penetrating further inland than they did a few decades ago. A rising sea and intense storms will increase the threat of erosion.

Coastal communities face both the direct challenges of a changing environment such as sea level rise, storms, and erosion, and the further impacts of a changing biota altering ecosystem service provision. An increase of just 1.1°C in global average surface temperatures poses a significant threat to small-scale fisheries, especially those who rely on coral reefs. Fisheries reliant on seaweed or mangrove environments will also face difficulties as temperatures increase.

Degree of damage

The Paris Agreement’s pledge to hold temperatures “well below 2°C” was a compromise between those arguing for 1.5°C and those who believe 2°C was acceptable. This report shows the clear difference in impact between those two levels. To avoid “catastrophic” levels of change, the report recommends the limit for warming be set firmly at 1.5°C.

As noted before, impacts of the current 1°C increase are already being felt. Between now and 1.5°C, and between 1.5°C and 2°C, many impacts will significantly worsen. For example, if warming reaches 2°C instead of 1.5°C, there will be 10cm more sea level rise by 2100. Storms will be more intense, and while coral already faces 90% die-off in a 1.5°C situation, in a 2°C situation shallow-water coral reefs risk almost complete extinction.

Additionally, there is increased risk, as temperatures rise, that irreversible tipping points will be reached. Sea level rise of some amount beyond 2100 is already certain. Thermal expansion of the ocean is reversible only on centennial timescales, and the collapse of ice sheets may be functionally irreversible. Melting permafrost could release more greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, accelerating warming beyond the modeled scenarios.

In addition to increased environmental damage, higher warming will also cause great socioeconomic changes. Urban areas face increasing risk of temperature related illnesses and morbidity as warming increases. Water scarcity will double in a 2°C scenario compared to a 1.5°C scenario.

The East Asian region faces increased precipitation, bringing with it increased flood risk. Southeast Asia is a global hotspot for precipitation increase between 1.5°C and 2°C scenarios. The 2°C scenario will also exacerbate issues regarding crop yields, and further damage sun and sea tourism for which Southeast Asia is a popular destination.

None of these risks can be isolated from the others. Environmental, social, and economic risks will all interact on local, national, regional, and international scales. It is likely that impacts will cascade, with the exact outcome dependent on many factors such as local conditions, preparedness, and response.

Necessary responses

The global response to climate change needs not only to be strengthened, but accelerated. The NDCs obtained at the Paris Agreement were an important show of commitment, but are not nearly sufficient to deal with the scale of the problem. Industries will have to be changed to shift towards low-carbon and no-carbon models. Lifestyle changes that lead to lower energy and land demands as well as lower greenhouse gas requirements for food will be critical as well.

However, reducing greenhouse gas emissions is not all that needs to be done. The greenhouse gases already in the atmosphere are enough to ensure a variety of environmental changes, and they will be added to by greenhouse gases released between now and the point where decarbonization is reached. Impacts of this requiring an adaptive response include sea level rise, storm intensity, and ecosystem alterations.

When examining possible pathways to decarbonization, the IPCC report examines how these pathways fit within the concept of sustainable development. Changes aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions and adapting to climate change’s effects should be included within an integrated sustainable development policy. Many actions that may be targeted at climate change will have societal co-benefits. For example, reducing emissions will lower levels of air pollution, improving public health and bringing economic benefits.

Possible changes can be grouped into three categories: adapt, migrate, and defend. All have different costs and benefits. In general, communities wish to stay in place, so governments are more likely to focus on adapting and defending. Sustainable development is not isolated to typical images of undeveloped areas. Megacities, especially coastal ones, are noted in the report as being extremely threatened by climate change’s impacts, and are crucial locations to implement changes in.

Efforts to mitigate climate change’s impact, through adaptation and defending, can have huge effects on at-risk areas. The report notes that planning for climate change needs to be integrated with plans for coastline management, enhancing the resiliency of coastal ecosystems and communities. A notably successful technique is mangrove forest restoration, which has shown benefits in numerous locations.

Many changes that are technically feasible are expensive and hard to scale. While climate change is a global problem requiring a global response, implementing adaptations requires partnerships with local communities and should be done with due regard to local cultures. At the smallest level, individual ability to adapt and change is often constrained by factors such as income, knowledge, and technical capabilities. Social and economic support will be important in implementing changes. Governments may have to encourage and aid alternative livelihoods, such as by investing in sustainable aquaculture.

The total investments required to decarbonize the global economy will require trillions of dollars over the upcoming decades. While large, this likely pales compared to the consequences of inaction. Knowledge sharing and technology transfer will be key to ensuring solutions scale. Multi-level governance is needed, as adaptations are needed at local, national, regional, and international scales. Cooperation will be critical, with horizontal collaboration between communities as important as vertical collaboration within a country. The report notes that regional cooperation will form an important component of global governance, and that climate change should become an integral part of transboundary cooperation.

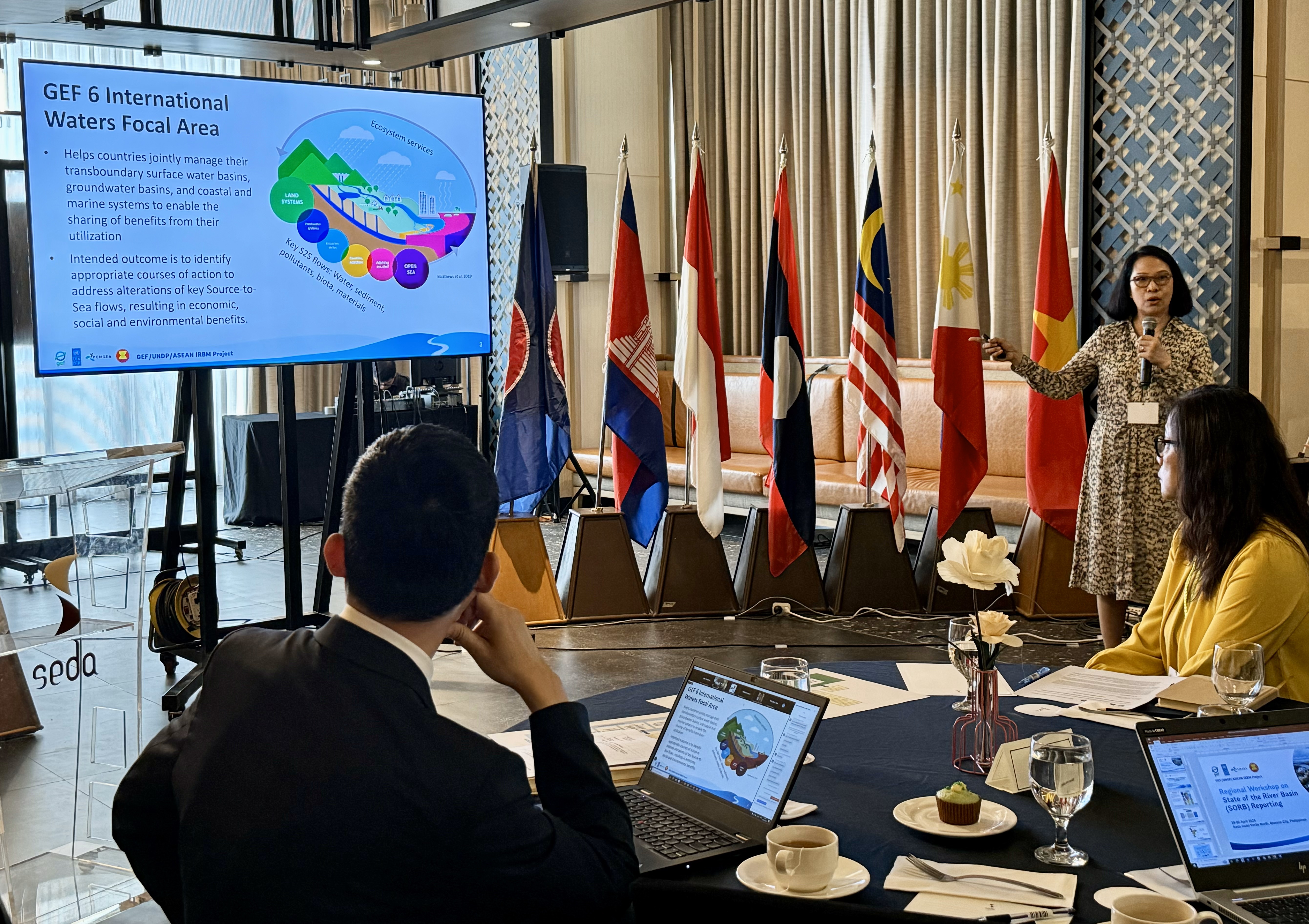

Involvement of PEMSEA

This report is obviously distressing in its clear and well-founded review of the challenges faced throughout the seas of East Asia and the rest of the world. Sea level rise and extreme weather events are already a challenge for PEMSEA partner countries and members of the PEMSEA Network of Local Governments (PNLG), and their intensification along with additional impacts is a significant threat to coastal communities throughout the region.

The challenges are formidable. However, PEMSEA believes such challenges are solvable. In its looking at pathways for change, this IPCC report contains strong validation for PEMSEA’s approach to the issues facing the region.

PEMSEA’s key approach of integrated coastal management (ICM) is exactly the sort of action that the report recommends. ICM demands a holistic approach and implementation to developing sustainable coastal communities. An integrated and iterative process is needed to bring about the large changes required to combat climate change. Sustainable development is needed to ensure that changes are supportive rather than impoverishing, especially for already fragile and at-risk communities.

PEMSEA also stands as an example of the regional transboundary cooperation called for in the report. The Sustainable Development Strategy for the Seas of East Asia (SDS-SEA) highlights that countries can come together to develop plans to manage and ensure the long-term future of shared commons. The PNLG represents horizontal collaboration at a local level, providing a forum for the spread of knowledge and best practices within the region.

The gap between actions needed and actions promised is large, and the gap for actions so far undertaken is larger. The need to reshape the world economy and society requires unprecedented change. This is hard reading. Nonetheless, despite examining the reams of alarming data submitted to the investigation, the IPCC report devotes a large portion of text to looking at pathways to securing the future. The best time to start moving down those pathways is now.