SDS-SEA Project: Lessons learned in the year of COVID-19

Friday, 26 February 2021

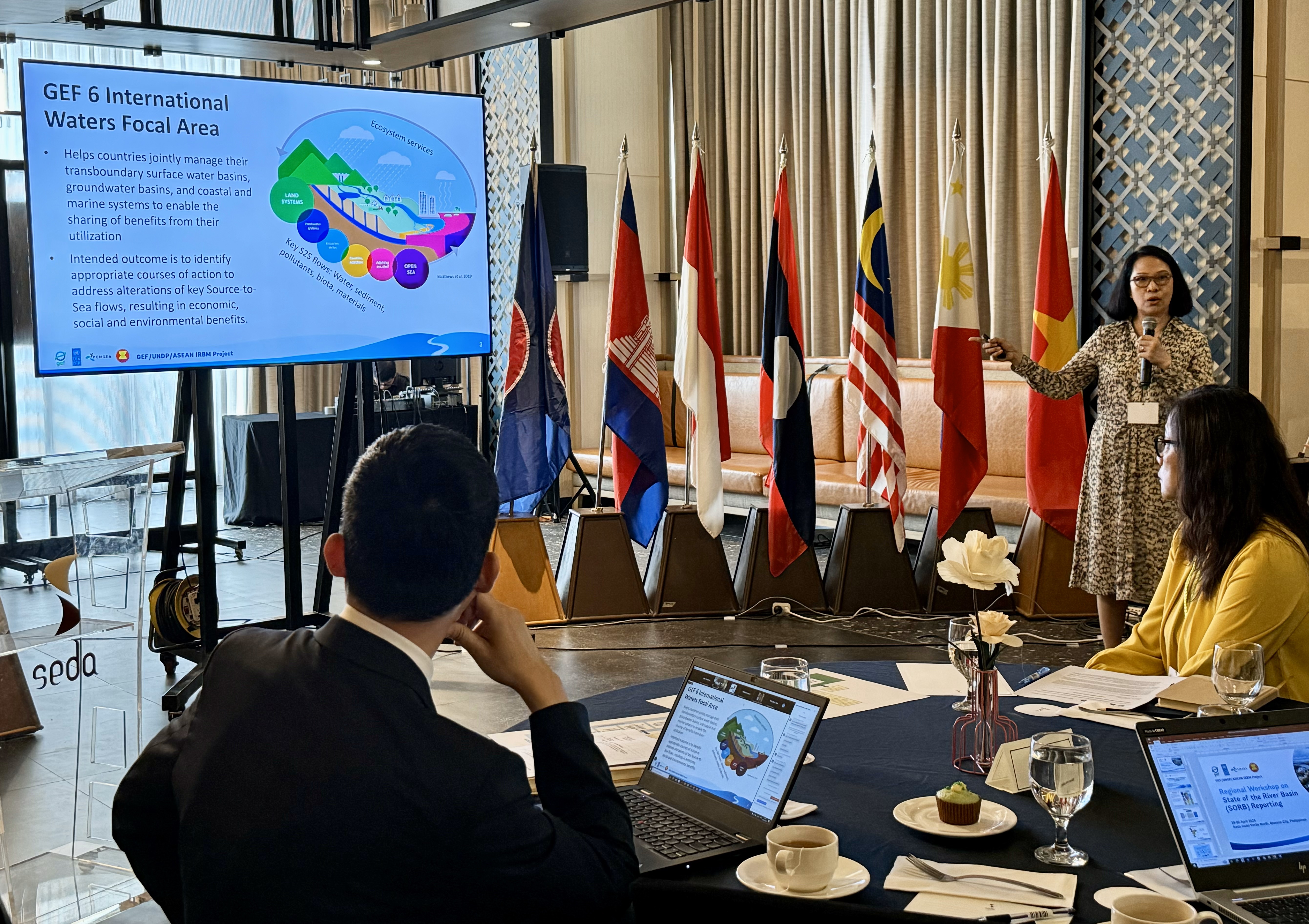

On December 2020, the GEF/UNDP/PEMSEA Scaling Up the Implementation of the Sustainable Development Strategy for the Seas of East Asia (SDS-SEA) Project reached a productive conclusion. The six-year project (2014-2020) aims to reduce pollution and rebuild degraded marine resources in the East Asian Seas (EAS) through the implementation of intergovernmental agreements and catalyzed investments. Participating countries include the governments of Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Lao PDR, the Philippines, Thailand, Timor-Leste and Viet Nam with Japan, RO Korea and Singapore participating on a cost-sharing basis.

The Project’s significant achievements include:

- establishing and sustaining a country-owned regional mechanism;

- strengthening National Ocean Policies and institutional support;

- expanding integrated coastal management (ICM) coverage in the region and replicating the tools, approaches and good practices beyond the region;

- developing innovative knowledge products and services such as planning and monitoring the state of oceans and coasts at the national and local levels and their role in promoting sustainable and inclusive blue economy, case studies in implementing integrated coastal management in the East Asian region and lessons in engaging with private financing and ocean economy;

- creating a regional knowledge sharing platform for ecosystems management; and

- contributing to global learning.

Several factors contributed to some delays in the delivery of the Project’s outputs. Issues on staffing, budget constraints, even political unrest, were cited by PEMSEA’s Country Partners.

However, perhaps the most disruptive event of 2020—the COVID-19 pandemic—was the biggest challenge encountered by all in the implementation of the SDS-SEA. The pandemic hampered the full completion of selected project outputs, particularly for reports and studies such as the State of Oceans and Coasts (SOC) Reports, where the results and recommendations need to be validated usually on a face-to-face arrangement.

The crisis triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic offers valuable lessons on how project implementation can still be effectively undertaken through remote and online work. It is anticipated that the pandemic will shape future planning, implementation and monitoring of projects by instituting adaptive measures that are proven to be working in the current crisis.

Key takeaways, best practices, and sustaining the SDS-SEA

Complex challenges facing sustainable development of coastal and ocean resources and ecosystem services require good governance, which is an integration of policy, legislation, education, financing, capacity building, education, science and inclusiveness/partnerships to effect change.

As project implementation is not a “one size fits all” arrangement, it is important to: (1) establish synergy and partnerships with relevant agencies and organizations with similar programs and build on their accomplishments for cost effectiveness and efficiency; (2) identify national and local leaders who can serve as champions; (3) recognize the contribution of partners and stakeholders and encourage greater participation; (4) showcase local benefits to create better appreciation of project impacts; (5) apply strategic adaptive management in cases where political or administrative conditions are affecting the project’s implementation; (6) carry on the required work, even after donor funding is terminated to ensure the project’s sustainability; and (7) invest in building entrepreneurial skills and capacity within PEMSEA and local partners.

PEMSEA’s Country Partners also shared some of the lessons learned from their implementation of the SDS-SEA Project:

- Cambodia: The key challenge was the building of robust institutional and human resource capacity at the sub-national level. This was recognized as a barrier at the start of the project, and was tackled with targeted capacity building and the use of external experts and technical advisers for capacity development of national and local personnel, and formulating and strengthening of community groups in support of the implementation of coastal and marine management activities.

- China: Some recommendations post project include further developments in the areas of blue economy emulating Xiamen, Qingdao, Rudong, Hainan and Dongying’s experiences in developing their respective Blue Economy Development Plans, adaptation to climate change, conservation and remediation of coastal biodiversity and ecosystems in support of the Blue Bay program and Ecological Redline Policy with GEF/UNDP’s continued support.

- Indonesia: The National State of Oceans and Coasts (NSOC) and local State of the Coast (SOC) reports provided a good basis for determining national and local priorities and needs; and the SDS-SEA/ICM Project implementation involving several agencies in the ICM sites was more beneficial under the coordination of the local Planning and Development Agency (BAPPEDA). The terminal evaluation report emphasized that BAPPEDA can make it easier to mainstream policies at the regional level (i.e., Indonesia’s Regional Medium Term Development Plan), and provide inputs to regional leaders in realizing their commitment to the implementation and sustainability of ICM programs.

- Lao PDR: A challenge was working with a large number of partners, and the need for more time for coordination, which caused some delays at the start of the Project. However, working with the same line ministry somehow eased the tasks of coordination and communication, as well as the prioritization of the needs of local authorities and their communities.

- Philippines: PEMSEA specifically targeted improving the capacity of provincial and local governments, a “bottom-up” approach built on a recognition that this focus is necessary to solve problems that originate at the sub-national level and should be continued for future project implementation. The terminal evaluation also provided recommendations for the national and local governments, GEF, UNDP and the PEMSEA Resource Facility (PRF) to sustain the gains of the SDS SEA Project and PRF’s operations for SDS SEA implementation. The evaluation noted the need for capacity building and training on ICM for staff and members of the Protected Area Management Board (PAMB) and the Protected Area Office (PAO) in support of the implementation of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources- Biodiversity Management Bureau’s (DENR-BMB) Coastal and Marine Ecosystems Program. The PRF can offer its services and enter into an agreement with the DENR to design and implement its ICM training and other capacity building needs. The Manila Bay Coordinating Office, which is responsible for implementing the Master Plan for Manila Bay, may also engage the services of the PRF to conduct an annual monitoring and evaluation of the accomplishments of the inter-agency task force assigned to implement the clean-up of Manila Bay. Other recommendations were for UNDP to continue to engage the services of the PRF for future GEF Projects, and to assist the PRF in securing an endowment fund to sustain PEMSEA’s work on ICM.

- Thailand: The terminal evaluation highlighted the partnership among the national and local governments, civil society organizations, private sector and communities in Rayong in managing and reducing wastes from the upstream to downstream areas of Rayong River and along the coast, and the capacity building of communities on waste segregation and management to support the operation of the Rayong integrated waste management center that converts municipal solid waste into refuse-derived fuel for energy generation. The SDS-SEA Project also supported the development of Chonburi’s Integrated Environmental Monitoring Program (IEMP), which engaged five agencies to develop a shared plan for systematic monitoring of the Chonburi coastal area.

- Timor-Leste: It would be important to have sufficient involvement of scientists in the ICM sites to observe progress, communicate at the national level, and integrate their findings in policy development. As it stands, the PEMSEA ICM Learning Centers have very limited resources, and their participation in the project activities were facilitated by consultancy contracts for baseline studies or trainings. It was recommended to continue the engagement with the ICM Learning Centers in relevant project activities especially in scientific monitoring and research related to blue economy and other national and local priorities.

Viet Nam: Expectations on targets on developing national sector legislative agenda and priorities, and incorporating SDS-SEA targets into national and local medium-term development and investment plans, should be tailor-fitted to the country’s capacity and resources to ensure the Project’s success. Funding for meetings or workshops should be reduced, and should be channeled instead to implementing field activities.

Building on the achievements of the Project, it is important to note some key elements that would help sustain the gains under the SDS-SEA implementation and scaling up. This includes: sustainability at the country and local level through the institutionalization and mainstreaming of ICM into the development and investment planning of the national and local governments; continued capacity building, networking, monitoring and evaluation; as well as assessment of ICM effectiveness and impact.

A full report on the project’s accomplishments, lessons, case studies and sustainability measures will be available at www.pemsea.org in April 2021.